Jules Renault on Redefining the Music Documentary, Drake’s 100 Gigs, and the Art of Creativity

- Nada Armanious

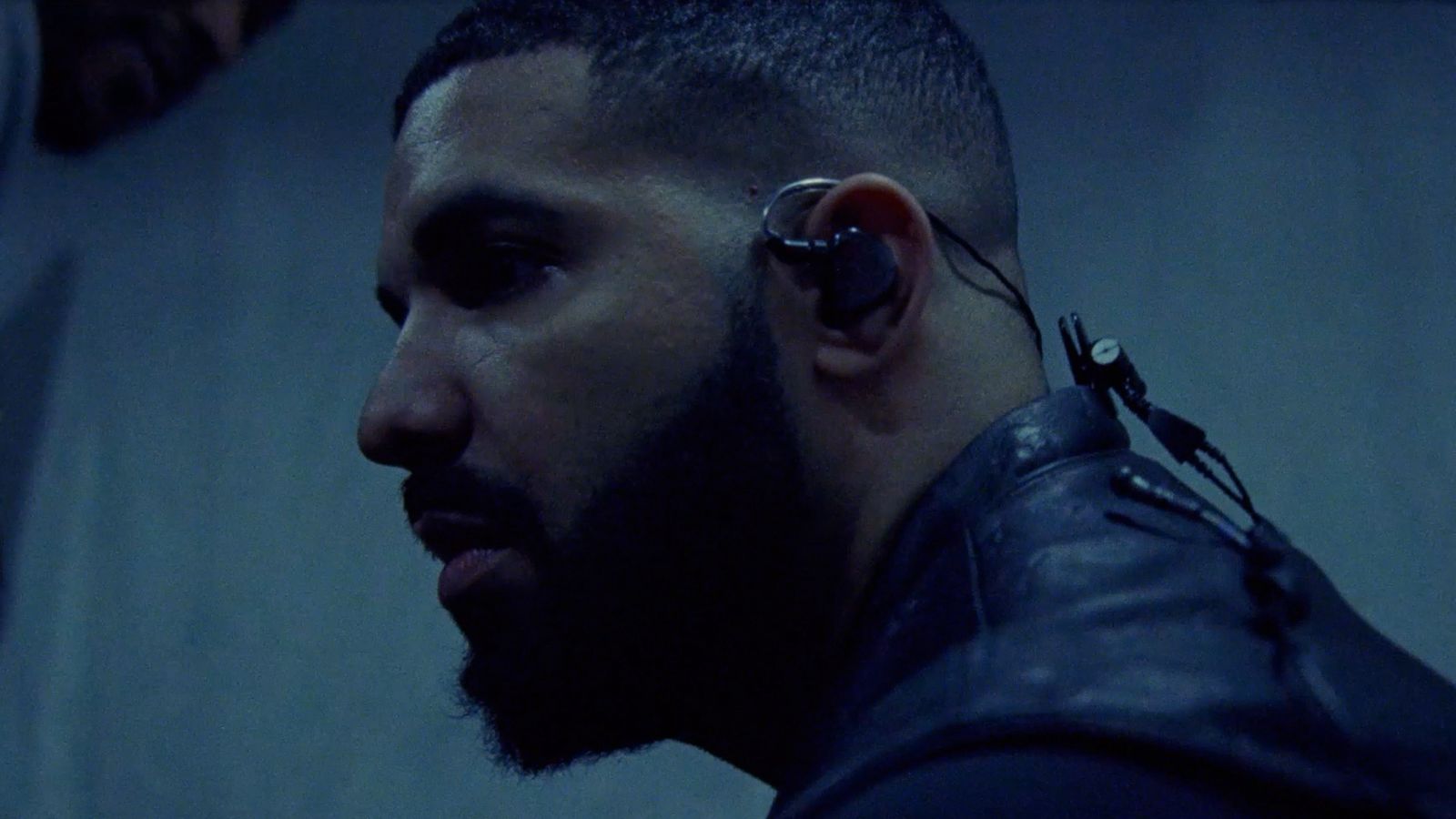

When Drake released 100gigs.org—a digital trove of over 100 GB of personal footage spanning studio sessions, backstage moments, private flights, and unreleased material—few could have imagined it becoming a cohesive visual project. But French director Jules Renault did. Known for his genre-blending style and ability to distill chaos into emotion, Jules took on the challenge of transforming the massive archive into 100 Gigs, a 20-minute experimental film that sits between music video and documentary.

Ahead of its exclusive premiere at Le Grand Rex in Paris, followed by an immersive Dark Lane Demo Tapes listening experience, we spoke to Jules about his creative process, artistic instincts, and how skate videos, commercial campaigns, and his refusal to be boxed in continue to shape his work.